27 December 2005

Birdseyes from

http://www.local.live.com

Related New York Times editorial, 27 December 2005:

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/27/opinion/27tues1.html

Editorial

Time for Chemical Plant Security

It is hard to believe, but more than four years after the Sept. 11 attacks,

Congress has still not acted to make chemical plants, one of the nation's

greatest terrorist vulnerabilities, safer. Last week, Senators Susan Collins,

a Maine Republican, and Joseph Lieberman, a Connecticut Democrat, unveiled

a bipartisan chemical plant security bill. We hope that parts of the bill

will be improved as it works its way through Congress, though even in its

current form the bill would be a significant step.

If terrorists attacked a chemical plant, the death toll could be enormous.

A single breached chlorine tank could, according to the Department of Homeland

Security, lead to 17,500 deaths, 10,000 severe injuries and 100,000

hospitalizations. Many chemical plants have shockingly little security to

defend against such attacks.

After 9/11, there were immediate calls for the government to impose new security

requirements on these plants. But the chemical industry, which contributes

heavily to political campaigns, has used its influence in Washington to block

these efforts. Senator Collins, the chairwoman of the Committee on Homeland

Security and Governmental Affairs, has held hearings on chemical plant security,

and has now come up with this bill with both Republican and Democratic sponsors.

The bill requires chemical plants to conduct vulnerability assessments and

develop security and emergency response plans. The Department of Homeland

Security would be required to develop performance standards for chemical

plant security. In extreme cases, plants that do not meet the standards could

be shut down.

Until recently, it appeared that the bill might include pre-emption language,

which would block states from coming up with their own chemical security

rules. That would have made the bill worse than no bill at all. New Jersey

has just imposed its own chemical plant security rules, and other states

may follow. These states should be free to protect their citizens more vigorously

than the federal government does, if they choose. To Senator Collins's and

Senator Lieberman's credit, the bill now expressly declares that it does

not prevent states from doing more.

The bill's biggest weakness is that it does not address the issue of alternative

chemicals. In many cases, chemical plants in highly populated areas are using

dangerous chemicals when there are safer, cost-effective substitutes. A strong

bill would require chemical companies to investigate alternatives, and to

use them when the cost is not prohibitive. Senator Lieberman has said that

he hopes to strengthen the bill's approach to alternative chemicals, which

would be an important improvement.

The burden now falls on the House of Representatives to pass a bill that

is at least as tough, and that does not pre-empt the states' authority in

this area. A leading antiterrorism expert has described the nation's chemical

plants as "15,000 weapons of mass destruction littered around the United

States." The American people have waited long enough to be protected from

these homegrown W.M.D.'s.

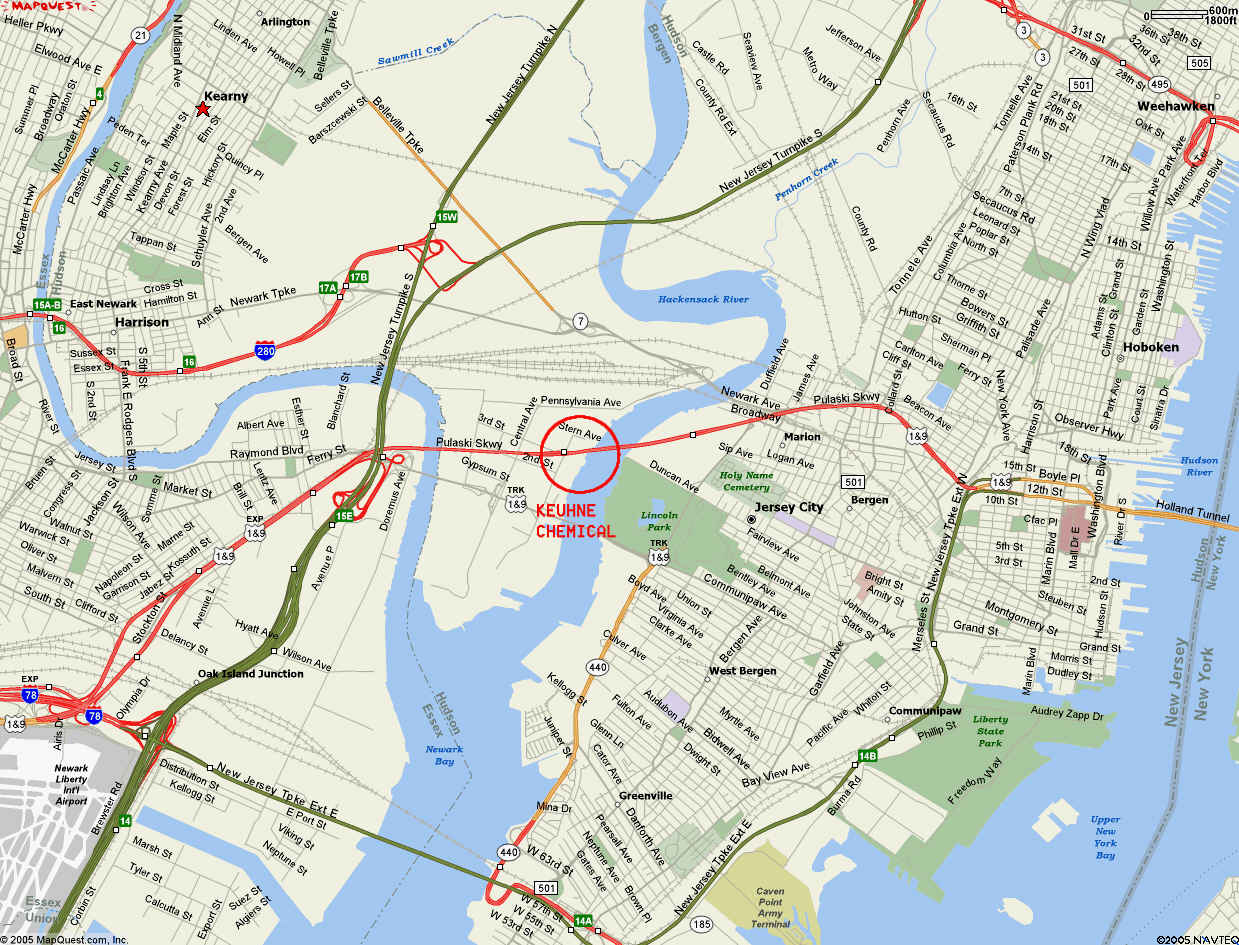

The Keuhne Chemical Plant, Kearney New Jersey, is judged to operate one of

the most dangerous chemical plants in the US.

http://www.govexec.com/features/0203/0203s2.htm

Easy Targets

February 15, 2003

Efforts to shore up America's infrastructure against another terrorist attack

have largely ignored a critical and highly vulnerable sector of the economy:

the chemical industry.

[Excerpt]

On an overcast September afternoon in South Kearny, N.J., Frank and Rosa

Ferreira parked their white Volvo across the street from the Kuehne Chemical

plant on Hackensack Avenue. Armed with a handheld video camera, the two

environmental activists wandered around the perimeter capturing images of

the plant's guard gates and security fence. They zoomed in on large storage

tanks labeled "sodium hydrochloride" in bold black letters.

A panoramic view of the fence shows security weaknesses in certain areas,

particularly at three entrance and exit gates, which are loosely held closed

by chains. No padlocks are noticeable. Despite scanning a couple hundred

yards of fence, the Ferreiras didn't pick up any security personnel on the

20-minute video, which they posted on their Web site,

www.publiccitizenonline.com.

Two days later, on Sept. 5, 2002, the Ferreiras returned. Again, they

photographed large chemical storage containers and idle tanker trucks sitting

a few feet away from the fence. And again, no security personnel approached

the couple.

Driving along the Pulaski Skyway, Frank Ferreira noticed another weakness

at the facility: It sits directly underneath the 1.3-mile bridge connecting

Jersey City to Newark. The plant, which produces chlorine and bleach for

cities along the Eastern seaboard, is a mere three miles from Newark

International Airport and five miles from Lower Manhattan. It wouldn't take

much, Ferreira says, for someone to stop on the skyway and penetrate the

storage tanks using a rifle or other weapon.

"A few days before we went down there, we saw an article in our local paper

that Greenpeace was looking at the safety of the chemical industry," Ferreira

recalls. "They focused on the Kuehne plant. The article talked about documents

filed with the Environmental Protection Agency showing that a chemical release

could threaten the lives of 12 million people in a 16-mile radius. We went

down there expecting to see something like Fort Knox - something you couldn't

penetrate." He was wrong. "It was like a ghost town. . . . Once we finished

taping, I turned to my wife and said, 'There is something terribly wrong

here.'"

The Most Dangerous US Chemical Facilities:

http://cryptome.org/0001/chem/chem-danger.htm

|